Jayhawks in the Olympics

Stories

BY: BRADEN SHAW

July 20, 2020

For the first time in his college career, Pete Mehringer was lying on the mat in defeat.

Failure was foreign to the 22-year-old Mehringer. Losing to Northwestern’s Jack Riley in the 1932 Olympic qualifying tournament was unexpected.

Mehringer had worked toward this moment and this stage his entire life. He taught himself how to wrestle using the “Frank Gotch and Farmer Burns School of Wrestling and Physical Culture” pamphlet. He then hitchhiked to the 1930 Kansas state tournament because his high school in Kinsley — population 2,270 — couldn’t afford to send him.

“There was nothing that was going to stop him from doing what he wanted to do,” Kansas Sports Hall of Fame Director Jordan Poland said. “That’s how he lived his life and that’s pretty evident from the things he accomplished.”

And he set out to accomplish as much as he could.

After college, Mehringer worked as a stunt double and stand-in in Hollywood. He was a stand-in for Herman Brix as Tarzan in “The New Adventures of Tarzan” in 1935. He also doubled for Bob Hope in the 1939 film “The Road to Zanzibar” where he was body slammed by a gorilla during a fight scene.

But before that, during his first two years at the University of Kansas, he had a successful wrestling career, with his only loss coming in the finals of the National Intercollegiate meet, where he first lost to Riley by decision.

But Mehringer and Kansas coach Leon Bauman felt Mehringer was still good enough to be an Olympian.

“If you have the opportunity to compete against the best, why wouldn’t you take it?” said Laura Hartley, public historian and former co-director of the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame.

After facing off in the National Intercollegiate meet — which Olympic wrestling coach Hugo Ottopok referred to as the “semifinals of Olympic qualifying” — the rematch with Riley came in the finals.

But instead of being 100% ready for his chance at redemption, Mehringer was involved in a car accident the night before. He also only had a 45-minute break between the semifinal and final matches of qualifying, while Riley had a bye.

Regardless of circumstance, Mehringer wasn’t one for excuses. Either way, his Olympic dreams were over, or so he thought. Instead, Ottopok gave Mehringer a second chance to represent the United States.

In a 1982 Kinsley Mercury story, Mehringer recalled Ottopok telling the team: “Anyone who had won the trials that thought they were going to make the team were mistaken.”

However, there was still another twist for Mehringer.

“After the match, the coach asked me if I wanted to wrestle heavyweight or light heavyweight. I asked him what would do the team the most good,” Mehringer said in the Mercury article.

Another way of putting it: Ottopok wanted Mehringer to lose 17 pounds to qualify for the lower weight class. The 1932 Los Angeles Olympics were only 12 days away.

Just before he cut the weight, though, Ottopok set up a rematch between the two rivals at the Olympic qualifying arena. Only Mehringer, Riley and Ottopok would witness the match.

This time around, there was no decision. Mehringer pinned Riley twice in six minutes. Riley would wrestle as a heavyweight.

During the next 12 days, Mehringer went through a physical and emotional transformation. He commuted from Lawrence, Kansas, to Los Angeles, taking breaks at rest stops and gas stations to work out. Mehringer also got married just a few days before the Olympics but the nuptials came with an ultimatum.

“Frances told me that if I didn’t win a gold medal, I need not come back to Olathe (Kansas),” Mehringer said in a 1984 interview with the Johnson County Gazette.

When the Olympics finally began, Mehringer was down to 189 pounds and set to compete for the U.S. team.

“It was terrific being in Los Angeles for the opening day ceremonies — to see the lighting of the Olympic torch,” Mehringer said in 1982. “But, being a farm boy, I didn’t realize just what the Olympics were. I thought it was just another tournament.”

Mehringer was the youngest competitor in the freestyle light-heavyweight division where he pinned his first two opponents, including 1928 Olympic gold medalist Thure Sjostedt of Sweden, and advanced to the finals against Australia’s Eddie Scarf. The “Kansas Whirlwind” won the decision to capture the gold.

“It’s something that would never be repeated today,” Poland said.

After becoming an Olympic champion, Mehringer returned to Kansas, where he become an All-Big Six tackle for the football team, and later became a member of the first all-star college team in 1934. After college, he played professional football for 13 seasons in Chicago and Los Angeles. His acting career was short-lived but besides working with Bob Hope and Bing Crosby on “Zanzibar,” he also was a stuntman in “Knute Rockne All American” (1940) that starred Ronald Reagan.

“[Sports] was a way to make a living, and he was good at it,” said Janice Mehringer, Pete’s granddaughter. “And he tried to be as good at it as he could.”

Once Pete left athletics, he later worked for the Los Angeles Board of Public Works, serving as a senior inspector from 1948-67. He died in 1987 while living in Pullman, Washington, but was buried in Saint Mary’s Catholic Church Cemetery in Hodgeman County, Kansas – about an hour from his hometown.

“He was always his own person at heart,” Janice said. “He charted his course and stuck to it.”

To this day, Mehringer is considered the greatest wrestler in Kansas history, and one of the university’s finest athletes. He is a member of the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame and the National Wrestling Hall of Fame.

“What Pete did was he worked his ass off every day to achieve his goals,” Poland said. “And I think if we take that lesson and apply it to our lives, I think we’d all have a little Pete in us. And, I think we’d all be a little better for it.”

BY: MARCELLA REEDER

July 20, 2020

The 2020 Summer Olympics is moving to July of 2021. And as the 33 sporting events are being changed, the music and bands will also be facing changes.

After a growing concern from the worldwide spread of the COVID-19 virus, the President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Thomas Bach, and Japan Prime Minister, Abe Shinzo, came to an agreement to delay the Tokyo Summer Olympics.

Bach sent out a video in response to the delay saying, “Dear fellow athletes, let me start with the good news first. We all will be able to celebrate the olympic games tokyo 2020 even if it’s in 2021… Today I had a telephone conversation with the prime minister Abe. There we agreed in the analysis of the development of the virus in the last couple of days, where we see a dramatic increase and outbreak in Africa, in South America, in Oceania and many parts of the world.”

Some events stayed according to plan like the flame-lighting ceremony that took place on March 12. The HOC (Greek Olympic Committee) announced some changes in the ceremony such as a cancellation to receptions, dinners and lunches, limitations to the event’s attendance and no fans to be at the final rehearsal of the March 11 ceremony.

The IOC replied to the continuation of the ceremony saying “At the same time, the world is facing challenges that are also impacting sport. But with 19 weeks before the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020, the many measures being taken now by authorities all around the world give us confidence and keep us fully committed to delivering Olympic Games that can bring the world together in peace”

Within every single Olympic Games, there are five parts towards the opening ceremonies. These openings fully announce the commencement of the Olympic Games. The Artistic Programs represents the celebration of sports and the message of bringing people together no matter the culture, religion, or heritage. The Parade of Nations shows all players of their respected nation being involved in the Olympic Games. The Traditional Events follow traditions that had been set in the 1900 Games of the II Olympiad in Paris, having the official start of the Olympic Games. The Olympic Flame is the tradition of a torch being run into the stadium by an athlete of either the host country or who is very well known. Lastly, the Doves symbolizes peace and has been shown in every Olympic Games after World War I in the 1920 Summer Olympics.

During the Olympic Games, music is seen to be one of the most iconic and traditional pieces during the whole commencement. Depending on the host country, the music being played will be catered towards that nation’s culture in music. The most iconic song that is played during the Olympics is the Olympic Fanfare and Theme by John Williams. Live bands have played the fanfare since ABC began using the familiar tune for its televised coverage of the Games in 1968 that took place in Mexico City. Williams and a live orchestra were able to conduct this piece and more during the Tokyo Games in 1987. It is without a doubt that this special piece of music will always be displayed in every event as it is an icon of all Olympic Games.

Looking at next year, it is uncertain if there will be live music and bands at the 2021 Games due to the events of Coronavirus. Preparations are being put in place by the Organizing Committee that includes finalizing the concept for the opening and closing ceremonies. What can be expected for now is the venue being held at the New National Stadium for the closing ceremony. What can be promised is a historical event that the entire world is looking forward to.

BY: JAKOB KATZENBERG

July 20, 2020

Not all stories of Jayhawks in the Olympics end in triumph. For sprinter Cliff Wiley, his was cut short due to a political stance taken by the United States government.

In January of 1980, there were rumblings of the U.S. potentially boycotting the Moscow Olympics to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Despite the rumors, qualifying events continued as scheduled.

“(President Jimmy) Carter started signaling that if the Russians didn’t get out of Afghanistan by a certain date, then we wouldn’t send our Olympic team,” Wiley said. “I don’t think that many of us thought that could happen. We just took it as ‘that’s just something politicians would say.’”

At the previous Olympic qualifier, in 1976, Wiley was one of the younger competitors in the meet and did not advance. With more experience under his belt and having run on several national teams, Wiley was confident he could place in the top three and qualify for the Moscow.

Wiley won gold on a 4×100 relay team in the IAAF World Cup in 1977 and again at the Pan American Games in 1979. He also posted a 200 meter time that landed him Top 10 in the world.

Stanley Redwine, the current coach of Kansas’ track and field team who competed against Wiley in the 1980 trials, said Wiley was somebody he looked up to at the event.

“I was young and didn’t really know what I was doing,” Redwine said. “I made the trials as a freshman in college. I had raced (Wiley) previously, because we participated in the Kansas relays. I raced against him. He was somebody I wanted to be.”

Wiley lived up to his expectations and finished in second place in the 200 meters, clinching a spot on Team USA.

“Making the team is an honor,” Redwine said. “Running in the games is an honor as well, but that is something that can never be taken from Cliff – he made the team.”

With the President Carter still speaking of a potential boycott and Russia refusing to pull troops out of Afghanistan, the U.S. competing in the Olympics started to look more and more unlikely.

“There was still a month to go between the trials and the games,” Wiley said. “I kept thinking to myself ‘something’s going to happen. There’s still a month, something’s going to happen.’ But, nothing ever did.”

With President Carter electing to go through with the boycott a decision was still to be made by the U.S. Olympic Committee. At the time, Great Britain was in a similar scenario – although their government wanted to boycott the Olympics, Britain’s Olympic committee voted to compete. Wiley hoped for a similar result in the U.S, but that never happened.

The USOC voted to go through with the boycott and Carter threatened to strip the passports of the U.S. Olympians if they attempted to travel and compete.

“When our committee voted not to go, that was kind of the death nail on it,” Wiley said. “As an athlete, you’d much rather lose on the court than have someone take if from you.”

In lieu of traveling to the Olympics, the qualifiers still were recognized for their accomplishments. In fact, Wiley said, it was arranged so each member of U.S. Olympic team received gold-plated congressional medals at the White House. Part of the trip included shaking hands with the President himself.

Although he felt distaste toward Carter, Wiley still showed him respect while he was there.

“I think that’s how most of the athletes felt,” Wiley said. “We go there – this person is a person of authority. Even though you may not respect them, you give the office that they occupy respect, so you shake their hand and you smile.”

To make matters even worse for Wiley, 1980 ended up being the only time he qualified for the Olympics. Unfortunately, he sustained a hamstring strain before the next qualifier in 1984. While he did compete, Wiley said the injury hindered him greatly.

“I made it through the first round OK,” Wiley said. “But, when I woke up the next morning I knew that I really didn’t have the strength, the conditioning, to get through all the rounds.”

Though Wiley said he still wishes he would have been able to compete for his country on the world’s biggest stage, he doesn’t feel like it overshadowed his overall career.

“I give a little bit more value than I used to over my accomplishments, instead of just dwelling on the fact that it was taken away from me,” Wiley said. “Not being able to (go to the Olympics) really hurt.”

*Note: In addition to Wiley, swimmer Ron Neugent and basketball players Lynette Woodard and Darnell Valentine were members of the USA Olympic team that did not get to compete in the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

BY: JASMINE PANKRATZ

July 20, 2020

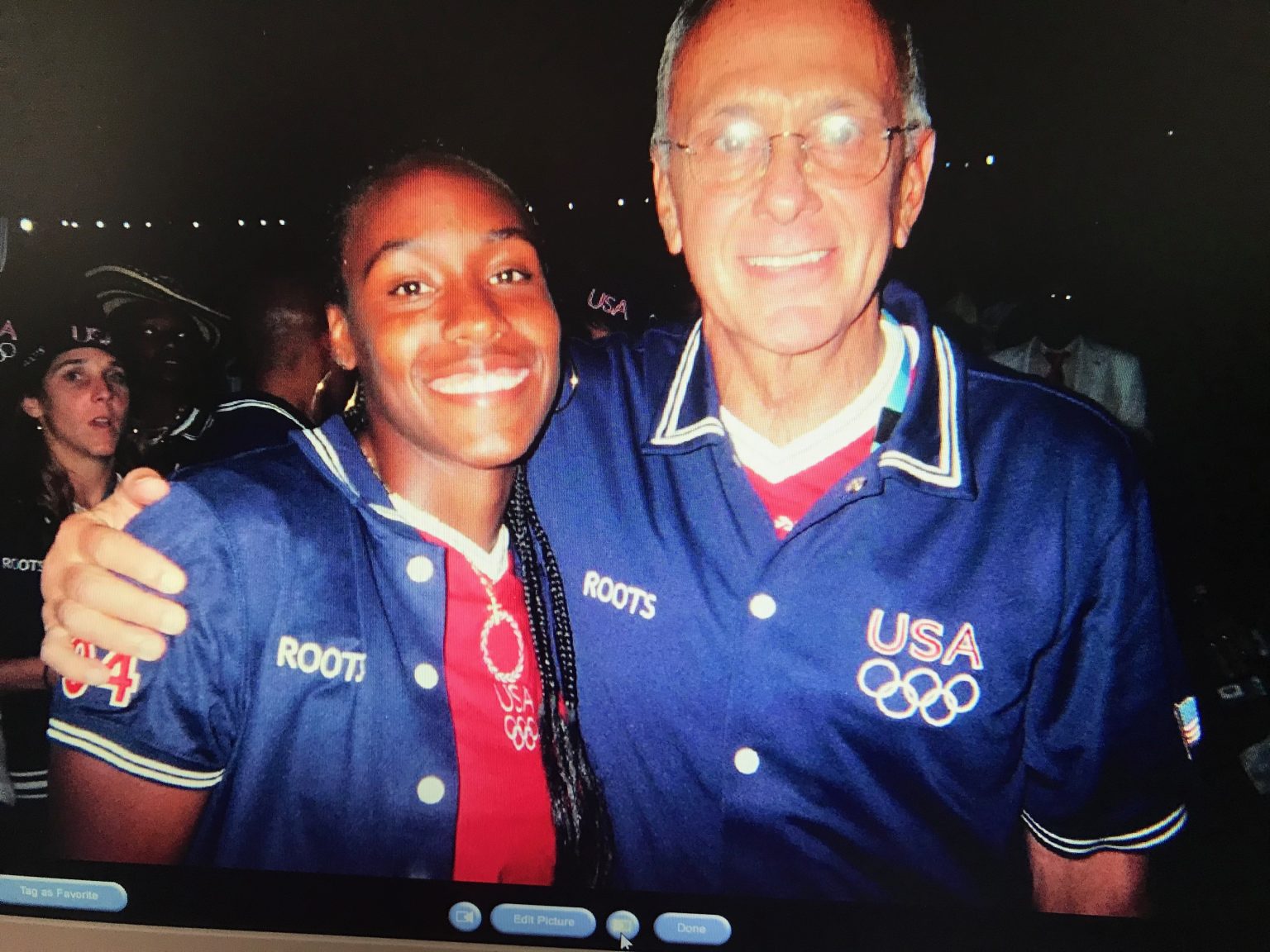

One of KU’s most frequent Olympians is not an athlete or a coach. However, you’ve probably seen him on TV in Athens, Beijing, London and Rio, waiting at the finish line.

Oh, and he helped the 4×100 women’s team win their historic gold medal at the 2016 Olympics.

On the final day of competition in Rio, he woke up, carefully stuffed his backpack with 16 beautiful American flags, and left the Olympic village to head to the stadium. He was upset that the games were almost over, but after a month in Rio, he was looking forward to getting back to regular life.

Upon arriving, he went down to the belly of the stadium where he spent most of his Olympic games looking at film and debating with officials over disqualifications. Normally, he would be at the finish line, handing flags to Team USA champions as they crossed. But due to a record number of protests and appeals throughout the games that needed dealt with, he handed off his flags to someone else.

All of the time spent down there paid off when the 4×100 women’s team stood on the podium to receive their gold medal. The team ran a historic 41.01 after they were granted a qualifying rerun because of a protest filed that forced track officials to give the U.S. another chance.

“That’s one of the prime services that I can offer athletes,” he said. “To go in and argue on their behalf to make sure that they get every right they’re due to compete.”

Tim Weaver grew up in Kansas City, competing as a sprinter and hurdler at Bishop Miege High School. He then went on to compete at the University of Tulsa before making his way to Lawrence for grad school to be an English professor. Weaver spent two years working with the sport he loved as a volunteer assistant track coach at KU.

As college students do, Weaver needed cash. So, he agreed to be the assistant meet director for the NCAA Division I and Division II cross country championships, hosted by KU at Rim Rock Farm in 1998.

That’s what changed the path of Weaver’s life, leading him away from teaching English to instead travelling with the greatest track and field athletes in the world.

After the Kansas Relays started losing interest in the 90s, KU looked for someone to revamp the event.

“They needed someone young, with energy, to take on that challenge,” Weaver said. “I was that young somebody with energy and free time. And I really fell in love with it.”

Significant changes implemented by Weaver led to the Kansas Relays becoming a stop for Olympic-caliber athletes looking to compete. Athletes like Maurice Greene, Justin Gatlin, Allyson Felix and many more made the trip to Lawrence for the Relays.

“We grew that event with a lot of help over a number of years,” Weaver said. “I saw an opportunity to grow something. With coaching, you can do that with individuals. I saw that same thing with growing relationships with alumni, in getting our track meets a little more efficient, and helping out every athlete on the track not just yours.”

In 2001, more than 30 Olympians competed at Memorial Stadium resulting in nine new meet records.

“Loving the sport, I tried to get involved on a lot of levels,” he said. “I was volunteering with USA track and field at some of their national championship events and I would go volunteer at the Penn relays to learn some of their ideas.”

Through those connections, Weaver was at the top of the list as someone to fill the role as manager for the world indoor team after the original manager withdrew.

“Based on my volunteer work, they said ‘Give Weaver a shot,’” he said. “From there I just loved it.”

And from there, Weaver served 21 International Team Staffs as a manager, coach or team leader, and as the assistant manager for the USA track and field Olympic Teams at the 2008 Games in Beijing, the 2012 Games in London and 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He will serve as head manager for the 2020 team.

During that time, he’s seen some of the best athletes in the world at the very peak of their life. Of course he’s seen the other side of it too, and while the buses are loading and the breakdown is happening, Weaver focuses on the well-being of the athlete.

“It’s about being there for those athletes whether they’re really high or really low if they maybe didn’t perform how they wanted or they’re angry, and they’ve just hit one of the big low points of their life.”

Weaver said that’s one of his most important contributions to a team, providing support for the total athlete experience.

“Being there to support the athlete logistically but also in their whole journey to the podium,” he said. “Whether that’s energy that we can provide, or mental support, or emotional support. Just making an olympic team as much a family as possible and putting the family first.”

That’s a concept that Weaver has tried to bring to every team he’s been on, the one team mentality. Which has proven difficult as athletes move from the amatuer level to the professional level.

“High school and college athletes are very much used to the team concept,” Weaver said. “Professionals may compete 25 times a year and only once in a team environment. It’s a big shift for those athletes to go back to a team mentality.”

Another challenge for professional track and field athletes that Weaver has to deal with is the dynamic that shifts at the Olympic village.

“At the Olympic trials it’s all about track, but then we get to the Olympics it’s also all about swimming and also all about weight lifting, and also all about basketball, and also all about gymnastics,” he said. “Track and field is one piece of a much larger machine.”

That’s one more job that Weaver has, helping athletes and staff understand the U.S. track and field team’s role in contributing to the “larger machine.” This means dealing with agents, sponsors and the media on behalf of the athlete.

“With 136 athletes, you have people going in any direction at any given time,” Weaver said. “It’s kind of a ten-ring circus but it’s a lot of fun.”

This year’s “circus” in Tokyo was going to be historic for Weaver as he was chosen to be a head manager for the first time in his career. Now, this year’s Olympic games will be historic around the globe as COVID-19 shows that even all of the muscles that attend the Olympics are no match to the virus.

“I really think the games are going to come about in a time where it will unify us because it’s something everyone can watch as every corner of the world is affected by the coronavirus,” Weaver said. “There’s stories that every corner of the world can tune into and can be connected by.”

Weaver believes that the legacy of the Tokyo games will be the ability to reconnect the world around something that is light and happy and where victories are pure.

“From the biggest countries to the smallest countries, part of that Olympic stage is for everyone,” he said.

On July 23, 2021, turn on the TV to watch history be made as the Olympics begin in Tokyo a year later than scheduled. Look for a Kansan at the finish line with a front row seat to history.

BY: EMILY NATWICK

July 20, 2020

Track and field head coach, Stanley Redwine is going to the Olympics. He will be serving as an assistant track and field coach for the United States at the Olympic Games in Tokyo. Although there is plenty of excitement leading up to the games, Redwine was clear about one thing.

“It’s all a great experience,” he said, “but I am a Jayhawk [first].”

Redwine said that he is not trying to deemphasize being selected as a coach for the Olympics. He enjoys coaching at any level and that having the opportunity to help anyone as a coach, especially as they represent the United States, is a huge honor.

Redwine is certainly qualified to be on the coaching staff for Team USA. The former All-American from the University of Arkansas has already landed his name in the Kansas Athletics Hall of Fame. During his 20 seasons of coaching at the University of Kansas he has coached one NCAA national championship team, 20 individual national champions, and many other athletes who have earned team and individual honors.

Although the Summer Games have been postponed to 2021, Redwine said that doesn’t change anything for him. The plan is simple and he knows what his role is while coaching.

“[I’m] just managing people more than anything. A lot of the athletes have their own personal coaches,” Redwine said, “but for those that are not there it’s just to carry out the plan of those personal coaches to those athletes. I’m not there to change the world.”

He wants to support the work that the Olympians and their coaches have already put in to get them to that level. Redwine said the worst thing that he could do is try to put himself in the middle of any of those athletes and their coaches.

When talking with Coach Redwine, it’s easy to hear how humble he is. He may downplay his role as a coach but the athletes he coaches at KU can speak to the atmosphere he has created during his 20 years as a Jayhawk.

“He is serious and committed in terms of putting athletes in the position to succeed,” TaeVheon Alcorn, a sprinter on KU Track and Field, said, “The kind of environment Coach Redwine creates is a winning atmosphere built upon support and family.”

For Redwine, it’s not about getting a certain coaching position to feel like he has made it in his coaching career; it’s about success. With the games postponed Redwine said that his focus is with KU right now. His goal is to earn another national championship.

“Well the highest height to me is for our team to be successful at the national level… Anytime that you can do that, that’s fun,” Redwine said.

He is committed to reaching the goals he’s set for himself as a coach and for his team. His combination of vision and competitiveness has led him and his athletes to succeed on the track.

“Every week at our team meetings, he talks about how we all have work to do to achieve our goals,” Alcorn said.

Alcorn said Redwine is key in keeping the team focused and ready to achieve their goals. Redwine’s coaching doesn’t end at athletic success though. He wants to develop the athlete as a whole, on and off the track. This creates a unique bond between him and those he has coached.

“There’s a relationship amongst all of us and I can call any of our past athletes and there’s a great relationship there, it’s not just for the time we’re here,” Redwine said.

Redwine’s goal is to teach the athletes he coaches how to mature and how to be better people once they leave. He said that is something they talk about from the beginning of the year, all the way through until graduation. Alcorn said this creates a tight-knit family environment that propels the team to excellence.

Redwine looks forward to traveling to Tokyo, looking to find a place on the podium for team USA. As ready as he is to coach at the Olympics, he said he knows his main role is with the crimson and blue. Redwine said it best, “I’m a Jayhawk through and through.”

BY: JASMINE PANKRATZ

July 20, 2020

The year was 1969. Legendary Kansas track star Jim Ryun was getting ready to run his last race for the University of Kansas at the Big Eight Championships in Ames, Iowa. Meanwhile, Jeff Jacobsen was making his photography debut.

Just a high school senior, Jacobsen was brought along to carry equipment, but instead was handed a camera and told to start shooting photos. He had never touched a camera in his life.

The next day the newspaper used one of those photos. From that point on it was all about photography for Jacobsen.

“I never looked back,” he said. “And I suddenly found myself sitting at the Final Four in 1970 and a year after that, photographing Kansas’ first time playing in the Astrodome.”

After preserving history through photographs for more than 50 years and spending the last 23 as KU’s sports photographer, Jacobsen is moving onto the next chapter in his life, but not before taking a moment to reflect on his past.

Jacobsen originally wanted to be a writer and went to the Topeka Capital-Journal looking for a job after he graduated high school. When no writing positions were available, photographer Rich Clarkson offered him a job working in the dark room. Clarkson was a legendary photographer who served as the director of photography at the Topeka Capital-Journal for 21 years.

Clarkson also hired KU photojournalism graduate, Jim Ryun. Yes, that Jim Ryun.

The two quickly became friends and fans of each other – for life.

“As the years went by, I eventually left the Journal and went to another Olympics,” Ryun said. “Whenever I’d return for the Kansas Relays, which was a number of times, I’d always look for Jeff. It’s always been a rewarding visit every time we have the opportunity to catch up.”

Jacobsen shot full-time for the Topeka Capital-Journal for 10 years before going to Phoenix as a sports photographer and then later returning to the Topeka Capital-Journal to work as the chief photographer for 13 years. In 1997, he started working at KU on an hourly basis and was offered a full-time contract in 2000 where he’s been at almost every KU sporting event since.

He shot KU winning the Orange Bowl and the men’s basketball team winning the National Championship in 2008. He’s shot 12 Final Four appearances, the baseball and softball team both winning the Big 12 Championship Tournaments in 2006, the volleyball team winning their first Big 12 title and countless track and field records being broken. He’s only missed four KU Relays since 1969.

And yet, his favorite KU moment is watching Jim Ryun compete.

“Anytime in the ‘60s when Jim Ryun was on the track are my favorite memories,” Jacobsen said. “But when Ryun ran a 3:54.70 mile at the 1967 Relays in front of a massive stadium crowd cheering wildly, that cemented my love of track and field that continues to this day.”

Ryun is just as much a fan of Jacobsen.

“Jeff is always looking for what will tell the story,” Ryun said. “More often than not, that requires some perseverance and digging to determine what will really tell the story. Yet at the same time, he’s very personable, he gets to know people and I think as a result of that, it opens the door for more creativity.”

And if anyone were to know what makes a great photographer, it would be Ryun.

In 1972, the U.S. Olympic Committee approached him while he was on an assignment for Sports Illustrated, working on a pre-Olympic issue with the 1972 athletes.

They told him he couldn’t be a professional photographer anymore if he wanted to compete because they didn’t allow professionals in the Olympics. He went back to New York and explained the situation so he could get out of his contract. At 25, Jim Ryun quit professional photography so he could be a full-time Olympian.

Whether it’s envy or just a pure admiration for photography, Ryun has been a longtime fan of Jacobsens.

“I admire his professionalism and ability to work around whatever circumstances are thrown at him and still provide what’s necessary to really tell the story,” Ryun said. “That’s a remarkable trait because it’s not always easy to capture the picture that will give the story perhaps what words couldn’t.

Jacobsen admits to being able to do what he does because he’s a fan of the relationships he’s made. He gives partial credit of his success to the athletes, but also the facilities workers, ushers and people working the gates.

“They make my job easier,” Jacobsen said. “Over the years, there have been people that have meant so much to me. I have a mental notebook in my mind of who my all-time favorite KU athletes are.”

That mental notebook is what helped Jacobsen to publish a book titled, “Tribute to Crimson & Blue,” with a foreword from Bill Self. His book features his best shots during his tenure at KU and gives insight to the student athletes in the photos.

But Jacobsen doesn’t only do it for the photos.

“I love to talk to people and part of it for me is also being a Christian,” he said. “I want to be a living example of what it means to be a Christian. And I want it to show in my photos, I want it to show in the way I treat people.”

In fact, he takes no credit for his photos at all.

“There are times I take pictures and I don’t even realize what I’m doing,” Jacobsen said. “I see my photos and it’s beyond my ability to comprehend how I took the photo. Because it was God. It’s purely God using me as a tool, as the photographer.”

Ryun believes that Jacobsen will continue to use the gift that God gave him, wherever he goes.

“Jeff’s been given a wonderful God given ability to take pictures, not everyone has that,” Ryun said. “I think that he’ll continue reaching out to others and doing what he can to improve their lives through the aspect of a camera and a lens.”

One would think that after 50 years of photography he’d be running out of new angles and photos would seem repetitive, but every sporting event is a challenge, an opportunity. He’s in no rush to stop being used as God’s tool.

“I’m looking for new challenges,” he said. “I have no intention of quitting taking pictures. I want to continue to do big projects and get to know new people.”

BY: COURTNEY MCMASTER

July 20, 2020

The son of a college discus thrower, Mason Finley always knew the Olympics was a personal goal. Learning techniques and throws since the age of 10, the Kansas City native was destined for stardom in the thrower world. The 6-foot-8, 325-pound, Finley has become one of the nation’s top throwers throughout his career.

At a young age, Mason’s hard work and physical presence paved the way to athletic domination in his track and field career. Growing up in Salida, Co. he attended Salida High School for his first two years and transferred to Buena Vista High School for his junior and senior year. According to Kansas Athletics in 2009, Finley was selected as the Track and Field Boys Athlete of the Year and held the national high school record in the discus (236-6 ft.). Finley racked up multiple gold medals that year in discus and shot put at the Nike Outdoor Nationals, Great Southwest Classic, Gold West, and the Pan American Junior Championships where he set a new U.S.A. Juniors record in the discus throwing 214-4 ft. In addition to those accomplishments, Finley is also a three-time Colorado state champion in both discus and shot put. With a resume full of accolades coming out of high school, recruiters were knocking at the door. Finley credits his immediate connection with Coach Andy Kokhanovsky as a reason for choosing KU.

In the 2010 indoor season, as a freshman, Finley was selected as an All-American in shot put; at that time being only the twelfth Jayhawk to be named an Indoor All-American. He also recorded five first-place finishes in shot put, winning the Big 12 Championship with a season-best throw of 19.25m (63-02.00 ft.) In addition, he competed in the NCAA Indoor Track and Field Championships and Kansas vs. Missouri Dual.

During his freshman outdoor season, Finley continued to rack up awards. He was named NCAA Midwest Regional Male Track and Field Athlete of the Year and the Big 12 Most Outstanding Athlete of the Year. During that season Finley placed first, in seven of the ten events he competed in, winning both discus and shot put at the Big 12 Outdoor Track and Field Championships. He also competed in and received second in both events at the NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships.

Coming off an impressive freshman year, Finley kept winning in his sophomore year. In the 2011 indoor season, he recorded the top shot put mark in the NCAA for the indoor season at the Kansas-Missouri Dual, placing first with a personal best throw of 20.71 meters In the same dual he won the weight throw with a personal best on a mark of 18.51 meters. Earning All-American honors in shot put at the NCAA Championship, he placed second with a throw of 19.92 meters. Finley also finished first in shot put with a meet-record mark of 20.40 meters at the New Balance Invitational where he was named field athlete of the meet. He also was the runner-up for shot put at the Big 12 Championship.

In the 2011 outdoor season, Finley “had one of the best seasons a thrower has ever had in a Kansas uniform,” according to Kansas Athletics. He was named to the USTFCCCA All-Academic Team, member of Academic All-Big 12 First Team, All-American First Team in both discus and shot put, Big 12 Champion in shot put and runner-up in discus. He finished the season with seven first-place titles in shot put and discus, with wins at the Big 12 Championship, Kansas Relays, and ULM Warhawk Classic where he set the school record for discus with a throw of 60.65 meters. Finley also competed and placed in discus and shot put at the USA National Championship and Would University Games.

After three years at the University of Kansas, Finley transferred to the University of Wyoming due to personal issues. He finished his collegiate career as an 11-time All-American, four-time NCAA runner-up, four-time Big 12 champion, and collected three All-Mountain West honors. After graduating in 2014, Finley continued to train and carried his energy to Eugene, Oregon, for the 2016 U.S. Olympic Team Trials for Track and Field. Finley’s dreams came true as he claimed victory and qualified for the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro.

In the 2016 Rio Summer Olympics, Finley competed in discus throw and finished 11th. Although he didn’t medal the whole experience was a dream come true for Finley. “It was crazy I got to meet all my idols and compete against them, in the same day,” said Finley. With his event being only one day during the Olympics, Finley took the time to explore Rio with his family.

After the Olympics, Finley turned his attention to the 2017 Track and Field World Championships in London. On his first discus throw he threw a personal record of 67.07 meters. On his second toss of the opening round, he once again set another personal record throwing for 68.03 meters. That throw was good enough for a bronze medal in discus, ending an 18-year medal drought in discus for the United States. The 26-year-old’s victory placed him in the record books, as only the third U.S. man to medal in discus at either the World Championships or Olympics. Although he made history by winning the bronze medal, his favorite moment was handing Coach Kokhanovsky a replica medal. “It awesome. He was an Olympian and never got a medal, so handing him the medal meant a lot to me.” said Finley.

Like many former Kansas athletes who have turned professional and continued training in Lawrence, Finley is currently a volunteer coach for KU’s track and field team. “Our current athletes are giving him [Finley] a hard time and making him up his game, at the same time they’re learning from him as they do, so it’s a win-win situation for us,” said current KU track and field head coach Stanley Redwine.

Finley hopes to once again have the opportunity to put on the United States uniform and represent his country in Tokyo at the pandemic delayed 2020 Olympics.

BY: LOGAN FRICKS

July 20, 2020

In the few years since Belarus entered the Olympics, the young country has made a name for itself in the men’s hammer throw. Now a new young star, Hleb Dudarau, also known as Gleb Dudarev, looks to be the face of the country at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics.

Dudarev arrived at the University of Kansas in 2016 as a member of the Kansas track and field team. Dudarev quickly made a name for himself that indoor season, receiving First Team All-American honors in the weight throw.

Dudarev finished sixth at the NCAA Division I Championships, throwing for 21.97 meters at the championships. Not only that, but he took the conference by storm, winning the Big 12 Indoor Championship after throwing for 22.02 meters.

In the outdoor season, Dudarev finished third in the hammer throw at the NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships, throwing for a mark of 73.44 meters, once again, receiving First Team All-American honors.

And like he did that same indoor season, Dudarev dominated the Big 12 by taking the crown with a school-record throw of 74.20 meters.

Before coming to the U.S., Dudarev had made a name for himself in Belarus. Dudarev attended Vitebsk State College and while there, he competed in the European Junior Championships in 2015. While there, Dudarev took ninth place in the hammer throw. Later that year, at the National Winter Throwing Championships, Dudarev took second in the hammer throw with a toss of 71.61 meters.

Dudarev, now a senior at Kansas, has racked up numerous awards, including six conference championships, four All-American honors, including three First Team, and a Kansas school record in the men’s hammer throw and weight throw.

The only thing missing off Dudarev’s list is an NCAA Championship. And if it wasn’t for the cancellation of the 2020 indoor season, Dudarev was nearly a surefire champion, holding the seven best throws in the NCAA in the men’s weight throw this year.

Unfortunately for Dudarev, the indoor championships were not the only thing cancelled either as the International Olympic Committee announced it would postpone the Olympics until 2021.

At the IAAF World Championships last year, Dudarev threw 76 meters in the hammer throw to place eight in the event. His throw was over two meters short of his personal record of 78.04 meters.

Currently, Dudarev ranks No. 9 in the world in the men’s hammer throw. He is also ranked number one in Belarus. He competed in the 2018 European Athletics Championships, nearly making the final, missing the cut by exactly one meter. Dudarev threw for a best of 72.19 meters at the competition, nearly six meters shy of the personal record he set back in April of that year. Had he been able to replicate his personal-best, he would have finished with a bronze medal.

Based on the success he was having in his senior year at Kansas, one could have expected to see improvements once the outdoor season came around. The young star could have very well continued his tradition of success at the 2020 Olympics, but now he will be playing the waiting game and will be forced to wait one more year before he can showcase his talent.

BY: JASPER HAWKINS

July 20, 2020

While in high school in El Paso, Texas, Diamond Dixon knew she wanted to become a runner after watching track championships on TV, according to KU Athletics. Dixon’s breakout freshman season as a Jayhawk flowed directly into Olympic success. She became the first KU student-athlete since Al Oerter, in 1968, to win an Olympic gold medal.

In 2011, as a freshman, Dixon received All-American honors in the 400 meters for her eighth-place finish at the NCAA Indoor Championships with a team record and personal best of 53.06. She also placed third in the 400 meters at the Big 12 Championships with a time of 53.10.

During her freshman outdoor season, she earned All-American honors and was the Big 12 Champion in the 400 meters, finishing with a time of 51.55. This time was a team record and personal best. She was named Big 12 Female Track and Field Athlete of the Week, earned Big 12 Track and Field Female Outstanding Freshman of the Year, and was named USTFCCCA Midwest Region Track Athlete of the year.

In 2012, during her sophomore season, she became an NCAA Champion in the 400 meters, setting an indoor school record for KU with a time of 51.78. She also claimed her second indoor All-American distinction anchoring the 4×400 meter relay at the NCAA Indoor Championships according to KU Athletics. Dixon was also the Big 12 Champion in the 400 meters with a time of 52.55. During this season, she also anchored the league champion 4×400 meter relay team which set a school record for KU with a time of 3:31.26. Again, she was honored as the USTFCCCA Midwest Region track athlete of the year, and claimed the USTFCCCA Female Track Athlete of the Year.

During the outdoor portion of her sophomore season, she earned her second-straight 400 meter Big 12 conference title with a time of 51.09. Dixon anchored the 4×400 meter relay team at the Big 12 Championships in which the team took first with a time of 3:28.10, which was a new school record for KU and the fastest time in the NCAA in 2012. She also claimed her third and fourth outdoor All-American distinctions during her sophomore year and was again named Midwest Region Female Track Athlete of the Year.

“Referencing the name Diamond Dixon in KU track is like talking about Mario Chalmers in KU Basketball. She’s a living legend,” said senior sprinter Chloe Akin-Otiko. “What she was able to accomplish has maintained the high expectations and history of success that defines KU track and field.”

Dixon qualified for relay pool at the USATF National Championships after placing fifth in the 400 meters. During her Olympic Trial run, she set a new school record and personal best time of 50.88.

“Just coaching her and talking to her and telling her she’s ready,” said KU track and field head coach Stanley Redwine. “I didn’t have to do much; she just was waiting on the opportunity.”

During the 2012 London Summer Olympics, Dixon ran on the preliminary 4×400 meter team. Her responsibility was to run the third leg of the race, which was a change from her usual anchor position. She ran a 50.15 during her leg, which was a personal best.

The U.S. 4×400 women’s relay team brought home the Olympic gold and although she did not run in the finals or get to stand on the podium, Dixon still earned herself an Olympic gold medal. She was the only NCAA athlete to win a gold medal in a track event at the 2012 London games.

“I think she probably should’ve been on the final four team,” said Redwine. “Diamond ran an awesome leg, she’s probably one of the most fierce competitors I’ve ever seen. You put her on a track, she’s there to win.”

In a 2019 interview with KU athletics, Dixon mentioned that Redwine had a lot to do with why she chose to come to KU.

“I knew I could go to any school,” she said, “but I ha[d] to have a coach that believe[d] in me.”

In an interview with KUSports.com, she revealed that Redwine was also the one to put the gold medal around her neck when picking it up from the airport. In this same article it was mentioned that Dixon did not accept her first-place prize money of $25,000 so that she could continue to compete for the Jayhawks.

“No point in me going professional right now,” she said to KU Sports. “If they want me now, they’ll want me then. I’m here to represent KU and take in everything I can while I’m here.”

Kyle Clemons, who won gold in the 4×400 relay at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games in a similar fashion, spent a lot of time on the track with Dixon. They ran the same event and often trained together.

“Intense is an understatement,” Clemons said. “She went extremely hard every time she hit the track. I never wanted her to beat me so that really brought out the best in me. Seeing Diamond win gold literally sent chills down my spine. The fact that someone doing the exact same workouts really inspired and lit a fire under me.”

Akin-Otiko agreed.

“She set the standards high for those of us who have followed after her and it is great to have such a role model in our program,” Akin-Otiko said. “Not every track and field program in America has or can produce Olympians and successful world-class athletes. That is what makes KU so special.”

BY: EMILY NATWICK

July 20, 2020

Many people are remembered for their success as an athlete, others are remembered for their acts of service for their country. Cliff Cushman is remembered for both. On campus, his name is forever in the KU record book and on the Vietnam War Memorial.

Dr. Bernie Kish, who teaches Sport Management classes at the University and is also a retired colonel in the U.S. Army, teaches a unit on Cushman to his students every year.

“Cliff Cushman had an amazing career at KU, alongside another track and field legend, Billy Mills,” Kish said. “He is certainly one of the many notable track and field athletes we’ve had.”

Cushman’s track and field career took him all the way to the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome but he’d been a start since high school. He grew up in Iowa and by his sophomore year he was already setting records. At the state track meet he placed first with a 4:27.5 mile. In the following year, his family moved to Grand Forks, North Dakota where he continued to shine on the track. He found his niche in hurdles but also had plenty of success in the middle distances, the relays, and the broad jump.

In 1956 he started his college career at the University of Kansas, running for hall of fame coach Bill Easton. Cushman became a versatile athlete, running whatever was needed from high hurdles to the three-mile run. His years competing for the Jayhawks overlapped with another future Olympian, Billy Mills. The two became good friends and by 1960, the senior Cushman was captain and led them to a national championship.

Cushman concentrated on the 400-meter hurdles in 1960 and earned himself a ticket to Rome to compete with the U.S.A. Track and Field team. The podium spots were all earned by Americans but Cushman found himself holding the silver medal, just 0.26 seconds behind his teammate Glenn Davis.

One week after the Olympics he reported to active duty for the US Air Force at the Craig Air Force Base in Selma, Alabama. While on duty he was training to be a jet pilot but off duty he was training for the 1964 Olympics. In the middle of all this he married Carolyn Throop. Cushman took a 30-day leave as the Olympic Trials approached, to focus on training.

“There were no hurdles on the base so Cliff came to Lawrence and worked out at Memorial Stadium,” Kish said.

The trials were nationally televised and Cushman was favored to qualify. Cushman was racing in the outside lane, tripped over a hurdle and fell to the side of the track. His dream of making the ‘64 team was gone.

The hometown hero of Grand Forks received many letters of sympathy after his fall. Cushman wrote them back in an open letter to the youth of Grand Forks. The message was don’t feel sorry for me. He wrote that he has seen a star, a goal, which was to get a gold medal in the Olympics and that he would give his all to reach it. He encouraged youths to cut their hair and to stop smoking in order to pursue their own stars. To this day Grand Forks Central High School still holds events in honor of Cushman.

He continued his training as a pilot in the Air Force and his training for the next Olympic Games. In November of 1965, Cushman and his wife welcomed their son Colin into the world. After completing his flight training for the F-105 supersonic fighter bomber in 1966, Cushman was sent to Korat Air Force Base in Thailand. Cushman was set to fly missions over North Vietnam. In September Cushman’s plane was hit during a bombing mission. They could not find his body and he was listed missing in action. It wasn’t until 1975 that Cushman was officially declared dead and presumed killed in action.

Following his death Cushman received multiple honors, including the Distinguished Flying Cross, two Air Medals, the Purple Heart, and the Silver Star. The Silver Star is awarded to those who act in combat with courage and bravery. It wasn’t the star he wrote about chasing, but he rightfully earned it.

Dr. Bernie Kish, who teaches Sport Management classes at the University believes Cushman is a true American hero.

“His life should be honored and celebrated forever by the entire Jayhawk family.” said Kish.

BY: JAKOB KATZENBERG

July 20, 2020

Following a long line of great player/coach duos, the relationship of Hall of Fame coach Larry Brown and forward Danny Manning led both to have decorated careers at Kansas and in the Olympics.

When you think of the two together, the first thing that jumps out to you is probably their NCAA championship run in 1988. After a rocky regular season in the Big 8 conference, the Jayhawks made the tournament as a No. 6 seed, only for the Brown/Manning duo to lead them to the national title victory.

Manning led the 1987-88 Jayhawks in nearly every statistical category, which led to the team nickname “Danny and the miracles.” While Manning was always a good player, he needed to elevate beyond that for the team to succeed.

Jeff Gueldner, who started on the team, said the bond between Manning and Brown was what turned them into a national championship winning team. He described Manning as a player who was at times “unselfish to a fault.”

“It was the constant prodding of Larry Brown that helped get Danny out of his shell to become great,” Gueldner said. “Danny was always going to be awesome but to be that transcendent star we needed to take us to a championship, it was the relationship (him and Brown) had that made it happen. They both knew that they needed each other in a way.”

Averaging 24.8 points, 9 rebounds, 2 assists as well as 1.8 steals and 1.9 blocks per game that season, Manning was perhaps the best college player at the time and had the 1987-88 Wooden Award, Naismith Award, NCAA Tournament’s Most Outstanding Player Award as well as Consensuses First-Team All-American honors to show for it.

After capping off his college career with a national title, Manning was selected to 1988 U.S. Olympic team.

“Nothing that he accomplished was a surprise,” Gueldner said of Manning. “He was obviously the best player in college basketball, No. 1 draft pick deservedly so. Being able to make the Olympic team, that was kind of the next national step for him.”

In the Seoul, South Korea, Summer Olympics, Manning was the third-leading scorer averaging 11.4 points and 6 rebounds in the eight games the U.S. played. After suffering a narrow 82-76 loss at the hands of the eventual gold medal winners, the Soviet Union, Manning and the U.S. took down Australia 78-49 to claim bronze.

Brown had been an Olympian himself, earning a gold medal as a player with Team USA in 1964. And after his coaching tenure at KU ended in 1988, he would return to the NBA and wound up coaching in two more Olympics. As an assistant coach in 2000, Brown collected another gold medal and as head coach, he led the U.S. to a bronze medal in 2004.

“(Brown) was very dialed in to the actual preparation for a game and he could draw up a play from scratch like nobody had ever seen,” Gueldner said. “Not everyone could play for him because his plays were constantly changing.”

At the 2000 Sydney Olympics, with Rudy Tomjanovich as the head coach and Brown as his top assistant, the U.S. captured the championship and Brown became the only man in Olympic history win gold both a player and a coach.

Danny Manning and Larry Brown could not be reached for comment

BY: JACK JOHNSON

July 16, 2020

Lawrence is a long way from Taichung, Taiwan, which is the location for the 2021 World Baseball Classic. The two are separated by nearly 7,500 miles, but the Jayhawks could have an alum representing them in the event. Brett Bochy, who pitched for Kansas from 2008-10, was added to France’s national baseball team roster in 2020. His father, Bruce, a manager for 25 years in the MLB with the San Diego Padres and San Francisco Giants, will coach France in hopes of dethroning the 2017 champion – the United States of America. The connection to France comes from Bruce, who was born in Bussac-Forêt, France.

“Brett’s had a lot of fun with this, too, having a chance to compete on the field again,” Bruce Bochy told MLB.com on his son joining France’s roster. “He didn’t step down from playing because of his arm, so we’re hoping he can help us in that bullpen. He wants to hit, too. He’s telling me, ‘I can help you off the bench.’ He’s been taking a ton of swings the last few weeks. We’ll have to see about that.”

It will be the second time the father/son duo will get to be on the same team on a professional stage.

Brett made his Major League debut with the San Francisco Giants on Sep. 13, 2014 against the Los Angeles Dodgers and became the first player ever to play for their father in the MLB. It would come in Bruce’s eighth year with the Giants and his 20th overall in the majors. Though Brett would crack the big leagues three years after leaving Lawrence, he struggled to maintain footing in the Bay Area. The right-hander would log only 6 ⅓ career innings with the Giants compared to his 262 ⅔ innings across all levels in the minor leagues. Brett did hold his own in the majors, however, posting a 0.789 WHIP and striking out 8.5 hitters per nine innings. Now at 32-years-old, Brett will get another shot to hurl off the mound after spending five years out of the league.

Looking back at Brett’s career at Kansas could be described as unique, but his journey to the heart of America wasn’t as complicated as it may seem. Despite his ties to California, his father was a Jayhawk fan according to coach Ritch Price.

“Our players had a chance to meet Mr. Bochy and talk baseball with him,” Price said in an interview with the Oklahoman in 2009. “There’s not a finer man in this game than Bruce Bochy. He talked to our players about adjustments. He’s a huge Jayhawk fan.”

After Brett redshirted his freshman season in 2007, he would make 12 appearances and toss 24 innings for the San Diego Waves, a summer collegiate team in the Western Baseball Association.

But when he returned to Lawrence for his first season of play, his numbers were subpar. In 16 ⅓ innings, Bochy put up a 5.94 ERA. The following year was an improvement, but not enough to improve his draft stock. He was 5-0 and struck out 52 batters in 36 innings with a collective 4.50 ERA. It wasn’t until Bochy’s final year in Lawrence that Major League clubs saw his true potential. In 12 games, Bochy posted a 0.78 ERA in 23 innings with 34 strikeouts and just seven walks. Those numbers were good enough for the Giants, who selected him in the 20th round of the 2010 Major League Draft.

Bochy became only the 24th player from the University of Kansas to make it to the majors. Additionally, he will be the first Jayhawk to play in the World Baseball Classic if France qualifies. The team will be looking to qualify in the tournament for the first time, as they have been unsuccessful in the previous two and did not enter in 2006 and 2009.

The 2021 World Baseball Classic is scheduled to run March 9-23. For Brett Bochy, he will be looking to not only make history for Kansas baseball, but for a country looking for the opportunity of a lifetime.

BY: JACK JOHNSON

July 16, 2020

By the time Sasha Kaun left the Kansas basketball program in 2008, his legacy was already cemented. Playing in 135 games, Kaun was a four-year member of the Jayhawks’ frontcourt and capped off his career with a national title in 2008. Though he never averaged more than 20 minutes per game in college, the native of Tomsk, Russia would earn his chance to compete for his country in the 2012 Olympic games.

“I think {Kaun} was smart enough to realize he was an incredible player coming off the bench,” former college teammate and roommate Matt Kleinmann said. “He was so gifted and athletic. His willingness to be a team player and step back was really good for us and our team chemistry as a whole.”

Before his trip to London for the Summer Olympics, Kaun had spent two seasons in the EuroLeague with CSKA Moscow and played in the FIBA World Cup with Russia in the 2009-10 season. Though he played in just seven of the 10 games, Kaun averaged the third-most on the team at 10.4 points and second in rebounds with 6.3 per game. Russia would finish 7-3 and behind the United States, who thrashed its way to an unblemished 11-0 record. However, many of the players who participated in the FIBA World Cup would meet again two years later in London. And one of those players invited back was Kaun.

“When you’re playing in the league professionally you always know what to expect from other teams,” Kaun told Kansas Athletics in 2012 prior to the Olympics. “But when you are playing a competition like this internationally, teams come from all different places so it feels different. African teams play different, American teams play different, European teams play different, even South American teams play different.”

The 6-foot-11 center would play for a Russian team run by David Blatt, who would eventually coach Lebron James in his second stint in Cleveland from 2014-2016. But this team did not possess that type of talent or firepower. In fact, Rick Eymer of Bleacher Report wrote in an article on July 11, 2012, that the Russian team was “no longer the powerhouse they used to be.”

“The Russians, who finished ninth at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, have four players with NBA experience, another on the way to the NBA and four who played in China four years ago,” Eymer said in his article. “Andrei Kirilenko is the lone player in his 30s, and he’s exactly 30 with two Olympics to his credit.”

Written off as one of many countries with a minimal chance of slaying the beast in the United States, Kaun’s Russian squad morphed the slander into motivation. Working to a record of 4-1 with narrow victories over Spain and Brazil in pool play, Russia advanced to the bracket portion where they would face Lithuania in the first round. Though they managed to push past Lithuania, Kaun and Russia were defeated by Spain in a rematch 67-59, putting them in position to fight for the Bronze medal against Argentina and NBA legend Manu Ginóbili. By a margin of four points, the Russians pulled off the upset 81-77 and claimed the Bronze over the 2004 Olympic Gold medalists. For Kaun, he played in all eight games and tallied 62 points and 29 rebounds in 156 total minutes.

“I was so happy. It means everything,” Kaun said in an interview with Gary Bedore after the Olympics. “To be the first team in Russia history to go and win a medal is unbelievable. The way basketball has grown in Russia is fantastic.”

Three years after his performance in the 2012 Summer Olympics, Kaun signed a one-year deal with the Cleveland Cavaliers, who employed his Olympic teammate Timofey Mozgov and coach David Blatt. In his one and only season in the NBA, Kaun averaged 0.9 points, 1.0 rebound, and 0.1 assists. But like he’d done in college, he walked out on top with a championship ring.

During Cleveland’s championship parade, the now four-time MVP and 16-time All-Star LeBron James credited Kaun with helping win the title.

“A good friend of mine texted me the other day by the name of Mario Chalmers, and he said you know you can’t win a championship without a Jayhawk on your team,” James said at the parade.”I said damn you’re kind of right. I won two in Miami with you and I got another one here with {Kaun} being the ex-Jayhawk at Kansas.”

Kaun will be forever be remembered in Kansas’ and Cleveland’s championship history. However, his accomplishments with Russia in 2012 potentially top the list of accolades over the entirety of his storied basketball career.

BY: DENITA VICTOR

July 16, 2020

From Eldoret, Kenya to Lawrence, Kansas, Sharon Lokedi has traveled around the world to become an accomplished and decorated athlete. Lokedi ran both track and cross country for the University of Kansas. During her first collegiate race in 2015, she finished 6th in the 3000 meters. Lokedi led the Kansas team in all five of the races in that year. Her drive and ambition advanced her to also become a two time All-American in cross country. Her success didn’t stop there. She currently holds the record for both 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters at KU and placed 5th at the Big 12 Championship during her last year at the University.

In an interview with KU Sports, head track and field coach Stanley Redwine expressed how important Lokedi’s talent was to their team. “I mean, there is no way to replace Sharon,” said Redwine.

Lokedi went pro after her collegiate season in 2019 and is now running for Under Armour. She placed first in her professional road race debut at the 34th Carlsbad 5000 with a time of 15:48.

“I’ve always been someone who enjoys the moment,” said Lokedi in an interview after the Carlsbad 5000. “I make sure I have fun while doing it and now it’s time for me to focus on the other side of running.”

She was able to share this moment with her fiancé Edward Cheserek. He attended the University of Oregon where he won 17 national championships as a distance runner. Cheserek is also from Kenya and is training to compete for Team Kenya in the upcoming Olympics. Both Lokedi and Cheserek are currently living and training in Flagstaff, Ariz.

BY: STEPHANIE MORALES MACEDO

July 16, 2020

1968 was an eventful year worldwide with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr’s, the ongoing Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 and the controversial Mexico City Olympics.

Those 16 days in Mexico City changed the way the world would view each other forever, past sports. Issues within individual countries of racism, classism, xenophobia and poor political structure would come to light for all the world to see broadcasted live on television and for the first time of the Olympics in color and the first time a woman, Enriqueta Basilio, would light the cauldron at the opening ceremony.

But one of those controversies didn’t stem from something people had nothing to do with; it came from its geography. Mexico City sits at a high-altitude level of 2,300 meters (7546 ft), which is the highest altitude of any of the cities to host the Olympics to date. The high-altitude levels were an advantage for sprinters, but a disadvantage for long distance runners. It made it harder for distance runners to breathe, but since there was less air resistance, sprinters were able to get record-breaking times.

Jim Ryun was a distance runner in the 1500-meter race, and he said that he could feel the effect of the high-altitude levels. Ryun was able to get a silver medal for the United States while Kenya’s Kipchoge Keino won gold.

“The only problem was the thinness of the altitude,” Ryun said. “The altitude was just so challenging.”

The Mexico City Olympics were unique as it was the first Spanish-speaking country to host the Olympics. The Olympics would not take place in another Spanish-speaking country until 1992 when Barcelona hosted the games.

“It was a special moment,” Ryun said.

People around the world also saw Felipe Muñoz make Mexican history. Muñoz became the first Mexican to win a gold medal, in the 200m breaststroke. The 17-year-old Muñoz said that nothing motivated him more than to win in his hometown of Mexico City. When medals were given out and the Mexican National Anthem began to play, Muñoz felt so overcome with pride and emotion that he could not even sing the anthem.

Mexico City, along with many other countries, was hiding something from the world. Ten days before the Olympics, police officers and military troops shot a crowd of unarmed students at the Tlatelolco Plaza. University students in Mexico started a movement to protest against Mexico’s authoritarian government, but it was short-lived as the massacre of Tlatelolco killed hundreds and detained over a thousand protestors.

Robert Lipsyte was a reporter for the New York Times when he went to the Mexico City Olympics. He told NBC that he remembered going to Tlatelolco Plaza and seeing washed-away bloodstains on the ground.

“It was brown underneath,” Lipsyte said. “And of course what it was, was the bloodstains of where they [the protestors] have been murdered.”

Mexico was not alone in controversy as the United States was nearing the end of its Civil Rights Movement and African-American athletes were planning to boycott the Olympics in protest.

Former discus thrower Harry Edwards, a PhD from San Jose State University, started the Olympic Project for Human Rights with members such as Tommie Smith and John Carlos. With Martin Luther King Jr. supporting the boycott and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar not trying out for the United States Olympic basketball team, the world was paying close attention to what would happen next.

“Let me just say that I absolutely support this boycott,” King Jr said in a press conference in 1967. “This is a protest and a struggle against racism and injustice.”

After the Olympic trials in California, some of the demands from the Olympic Project for Human Rights were met. South Africa was banned from the 1968 Olympics because they were not allowing black athletes to represent their country. Additionally, black coaches would become part of the United States Olympic team. Harry Edwards decided to call off the boycott, but he knew that a statement had to be made in Mexico City for the whole world to see.

No one was prepared for what Tommie Smith, gold medal winner for the 200-meter, and John Carlos, third place in the 200-meter, would do after their victory. Perhaps one of the most controversial and memorable events of the 1968 Olympics took place on medal podium for 200-meter sprint.

The pair did not care about the medals. Smith and Carlos went to Mexico City to protest for the Civil Rights Movement by making a statement, not to celebrate.

“Now we can do business,” Carlos said in an NBC interview. “Let’s do what I came here to do.”

Smith and Carlos wore black socks with no shoes on the podium to show African American poverty in the United States. Both of them covered the Team USA logo on their race uniforms and Carlos wore beads around his neck to signify the history of lynching in the United States. Both wore a single glove that would be remembered forever.

During the national anthem, they rose their fists together. The United States Olympic Committee suspended Smith and Carlos and gave them two days to leave Mexico City.

The 16 days in Mexico City changed the way that people viewed Mexico and the United States. The 1968 Mexico City Olympics were a statement in Olympic history and would never be forgotten.

BY: BRADEN SHAW

July 16, 2020

Billy Mills is a man of many stories, a natural byproduct of living a life full of creating them. Pair that with his overflowing charisma and it’s no surprise he’ll gladly share life lessons he’s gathered over the years with anyone in hopes of imparting wisdom.

Current Kansas track and field head coach Stanley Redwine recalls one such moment, when he visited with Mills at the 2019 NCAA West Track and Field Preliminary. The former KU star took the coaching staff out to lunch, and Redwine recalls Mills talking about “what it takes” to compete at a championship level.

“We’re always understanding of what it was like and what it’s like now,” Redwine said. “His experience in Tokyo was probably like none other because of the times as an athlete that he was there.”

Inspiration and support go hand in and hand with Mills. For Redwine, anytime one has a conversation with Mills is “a fond memory.”

“The great thing about Billy is, he cares about the (current KU) program as well,” Redwine said. “And I think that’s one of the things that you can find about some of the KU alums that are really successful — they care about the current team.”

Much of that comes from Mills’ naturally selfless demeanor, but also the support he’s been shown throughout his life. And the majority of that support comes from the second half of the Mills power duo: Billy’s wife, Pat.

Their emotional tie is so potent to this day — an unsurprising fact given their marriage of over 50 years — that Billy has to regain his composure when simply talking about her.

“Just the way she looks at me and the sparkle in her eyes tells me her story. She believes in me,” Billy said. “So I have to try to put myself in a position where I can accomplish these dreams, the things that I think of.”

Pat has served as Billy’s agent and manager, booking him speaking engagements, leading their “Running Strong” foundation alongside him, and helping to share his life story in the film “Running Brave” and the book “Lessons of a Lakota.”

If that weren’t enough, Pat’s an artist in her own right, managing her own art studio. With so many things to juggle, it makes the strong partnership that much more important.

“He motivates me by just believing in me and kind of giving me a calm strength,” Pat said. “Sometimes I’ll get freaked out because I’m an artist, I’m creative.

“And I have a gallery, so I’m in a different world than he is. He kind of helps me settle down when I’m in my art mode.”

Much like how Pat creates her art, Billy has found there’s power in process — pivotal steps along the way to finding your passions and achieving your goals.

“That experience (in Tokyo) taught me that it’s the journey, not the destination that empowers us,” Billy said. “And it’s the daily decisions we make, not just the talent we possess, that choreographs our destiny.”

While that journey that resulted in winning Olympic gold in 1964 was self-fulfilling, Mills has always been focused on paying it forward. He wants to continue inspiring others, a belief that’s rooted in the Lakota virtue of the giveaway.

“For the people that empower you, you try to empower (others),” Mills said. “In Lakota traditions, the elders have the visions and the children have the dreams. So Pat and I wanted to empower the visions of the elders and inspire the dreams of the youth.”

Redwine points to Mills’ sincerity and wealth of knowledge as to why he’s become so inspiring to so many. It’s also helped him stay relatable even with his status as an Olympic icon.

“I wish I was older and was an athlete when he was competing because just seeing him makes you want to do the things that he did and accomplish the goals he accomplished,” Redwine said. “He’s just a great guy. Every time I’ve talked to Billy, he enlightens me with information.”

Mills and Redwine looked to reconnect once again in Tokyo for the 2020 Summer Olympics. And even though the Olympics were postponed to 2021 due to COVID-19, the two still look forward to the reunion, even if Redwine may have his hands full as an assistant coach for the U.S. team.

“I was looking forward to seeing him in Tokyo that many years later,” Redwine said. “So to support him is a compliment and just an honor for me.”

If nothing else, Millis will be able to share more stories while in Tokyo next year, continuing his lasting tradition of giving back the blessings he’s received over the years.

“I thought there was a responsibility as an Olympian (to promote) global unity, the dignity, the character, the beauty of global diversity,” Mills said. “Obviously things outside the Olympic Games are far more important to humankind.”

BY: DENITA VICTOR

July 16, 2020

Washington state native Andrea Geubelle always has had big dreams. She’s fast on the field, court and track.

Geubelle wasn’t always a triple jumper, she was used to running distance. It was her bounce that caught an eye during her volleyball game. One of her high school coaches saw the potential she had during her senior year and from there she became victorious.

She was ranked third in the nation for triple jump, won gold medals at the 2009 Nike outdoor nationals and even was the Gatorade Athlete of the Year in the state of Washington.

Moving away from home to continue her track and field career was an easy choice for Geubelle.

“I knew that I wanted to leave and fully emerge myself in growth and be able to focus on track

and field without distractions, said Geubelle. “I knew I could do that at Kansas.”

It was the support that got her further. Geubelle knew she had a strong support system of friends and family who believed in her. Her secure bond with assistant coach Wayne Pate brought confidence in her as well.

“I’m a big relationship builder and I know how important that is with your coach. From the get- go I knew Coach Pate and I had to be on the same page to be successful,” said Geubelle.

Geubelle competed at the 2012 Olympic Trials, but didn’t have a qualifying standard to make Team USA. That moment filled her with anger.

“There’s already so much pressure going into the Olympic Trials, it’s the hardest meet to make. The experience in 2012 lit this fire leading to 2016,” said Geubelle. “Physically 2016 was a hard year on me but mentally I was not walking out without making a team.”

She carried that fire into the 2016 Olympic Trials. She placed third in the triple jump with the mark of 13.95 meters qualifying her to represent Team USA at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games.

Geubelle roomed with Olympic veteran Kara Winger and credited her with helping to control their emotions, especially during the Opening Ceremonies.

“Your breath is just taken away,” said Geubelle. “It {was} the biggest personal moment in my athletic career.”

When it was time to compete, it was a whole other beast she had to fight. Around her were athletes who were the best of the best. She placed 21st in the triple jump and while she wasn’t initially proud of herself, she eventually realized the big accomplishment she had participated in.

The 28-year-old isn’t quite ready to call it quits. Geubelle is hopeful to participate in the 2020 Tokyo Games, which have been postponed due to the covid-19 pandemic.

“The biggest confidence I have is knowing that I’ve done this before,” said Geubelle.

Tokyo could be potentially her last time competing, but Coach Redwine thinks she still has more left in her.

“It’s still in her,” said Redwine. “I don’t know if she’s ready to give it up or not. From high school to becoming a national champion for KU and then to make the Olympic team, I think that is just an honor for her and her work ethic.”

With the hold in athletic competition, it is just a waiting game for things to get back to normal. With limited resources, Geubelle has been doing home workouts and trying new things like Zumba.

Before she makes an ultimate decision to continue competing or not, she says she’s got to listen to her body and see what feels right. Geubelle doesn’t think she will ever distinctly retire because she has huge dreams which include becoming a mother, starting her own non-profit company, and even becoming a professional golfer.

She also said there is more about her than just the title of being an Olympian. Her impact and being an inspiration to someone’s life is something she strives to be. Being an Olympian has given her the platform to share who she is and prove to people that no matter what your title is, there is much more to who you are.

“You look at Michael Phelps and Simone Biles,” said Geubelle. “These people who have achieved extraordinary achievements but at the end of the day they’re human.”

BY: DENITA VICTOR

July 16, 2020

St. Louis is the home to the arch, toasted ravioli and the 1904 Summer Olympics.

Some may have never guessed the Gateway to the Midwest would be the first American city to host this notorious competition. Initially, St. Louis was not the destination for these summer games. Chicago was the contender to host, but since the 1904 World’s Fair was already set for St. Louis, it was only right for both events to take place in the same city.

The Olympics lasted 146 days, starting from July 1st until Nov. 23. These games were the second-longest in history, behind only the 1908 London Olympics, which dragged on for 188 days.

Not as many athletes participated in 1904 and of the 651 competing, only six of them were women. There were 100 different sports, but archery was the only event in which women were allowed to compete.

Boxing, freestyle wrestling, decathlon, and dumbbells also made their debut as events in St. Louis.

Another first for the games were the three different medals. This was the first time

athletes received gold, silver and bronze medals. Team USA received a total of 239 medals, a record that still stands today. The Soviet Union was right behind with 195 medals.

Even though it was a worldwide competition, only 12 nations represented themselves at the games. Some of those countries included Canada, Greece and Germany.